After a storming debut for Maison Alaïa in Summer 2021 and an equally exciting Winter 2022 follow-up, Pieter Mulier is now diving into uncharted waters by launching the brand’s first ever swimwear line. A nod to Azzedine Alaïa’s Tunisian heritage, Mulier’s sculptural pieces tell a larger story.

Alaïa 2022 swimwear campaign. Source: tag-walk.com

From the couture salon to the Côte d’Azur

Alaïa is neither the oldest nor the most expensive brand on the Paris scene, but it’s arguably the most prestigious. Mulier described his appointment at the helm of Maison Alaïa in February 2021 as “winning the lottery”. It’s “the holy grail for anyone who works in fashion,” he told i-D. His new swimwear collection is both a tribute to Azzedine Alaïa’s sculptural silhouettes and a testament to his own talent for pastiche. Since joining the maison, Mulier has been passionate about paying homage to the brand’s roots.

The bathing suits feature instantly recognisable staples, including studding, eyelet, zips, leather, and the signature open-knit design. At once comfortable and figure-hugging (in true Alaïa fashion), the items include high-cut one-pieces, bolero-style swimming jackets, and two-piece bandeau bikinis with longline midi skirts to match. Coming in white, sky blue, dark green, maroon, and red, these veritable pièces de résistance are a welcome – if overdue – addition to the Alaïa canon, where bodycon corsetry and leotards have rubbed shoulders with pleated skirts and animal-print coats for close to fifty years.

For a high end label to create swimwear is not unprecedented. Perhaps the most famous example dates back to 1994, when Claudia Schiffer and Christy Turlington waltzed down the Chanel runway in black bikinis bearing the interlocking C logo. But Alaïa is a maverick brand: esoteric, unorthodox, and famous for playing by its own rules. Every artistic decision carries a stronger cultural resonance than it would at a more corporatised label. The swimsuits require no logos to identify their provenance. Like the women who will no doubt wear them, they are poised, alluring, and impossibly chic. As Mulier put it in an interview with Another Magazine: “Alaïa is the only house that can do sexuality without being vulgar.”

The only sign of the Alaïa name is found in the ever-glamorous campaign, shot and directed by Albert Moya, which presents the swimsuit collection in action. Women are shot from an aerial viewpoint, diving into a turquoise pool where a large, black, all-cap logo seems to engulf them as if by osmosis. The campaign plays off something of a metaphorical irony: Alaïa is one of those rare brands which has not, in fact, been engulfed by logomania.

Keeping things old school

Interviewed by i-D, Mulier identified Alaïa as a traditionalist haven within the increasingly chaotic landscape of luxury. Indeed, it houses a small and devoted team of highly skilled technicians and dressmakers, with ateliers for tailoring, leather, and dresses. The staff totals 24 and includes two generations of the same family. Azzedine Alaïa was adamant about employing seamstresses and stylists with impeccable pedigrees, some of whom were trained by none other than Cristóbal Balenciaga. When Yves Saint Laurent’s couture line ceased in 2002, he snatched up fifteen members from their former workrooms. Many are still with the company today, including Alaïa’s first ever assistant, Hideki Seo, a Hiroshima-born artist. For Mulier, Maison Alaïa is “about clothes and humans”: “It’s not about fashion, it’s about construction, about making women more beautiful.”

Construction is the operative term when it comes to Alaïan dressing. The Tunisian designer famously referred to himself as a bâtisseur: a builder of clothing that was architectural in scope and vision. He bypassed the initial sketching stages of the classic dressmaking process, allowing outfits to find their groove during fittings on models and mannequins. His unique approach to tailoring and deft ability with fabric spoke not only to an awareness of different female body types, but also to a greater desire to sublimate and empower women.

Alaïa was a couturier in the most traditional sense of the word: a man who made clothes-to-order for the aristocratic set, counting Marie-Hélène de Rothschild among his clients. When the ready-to-wear phenomenon burst onto the fashion scene in the 1970s, Alaïa stayed in tune with the times by creating more affordable lines. Yet he continued to bring a similarly haute level of craftsmanship to whatever he created. His clothes, quite simply, don’t wear out. When Naomi Campbell interviewed Christy Turlington on her video podcast ‘No Filter With Naomi’ in April 2020, she immediately drew attention to her outfit: a beige knitted dress with floral ornaments made by Alaia in the early 90s. Campbell tugged and pulled at the dress to emphasise its resistance, commenting: “This fabric should be floppy, and it’s not: it’s still tight and resilient as ever.”

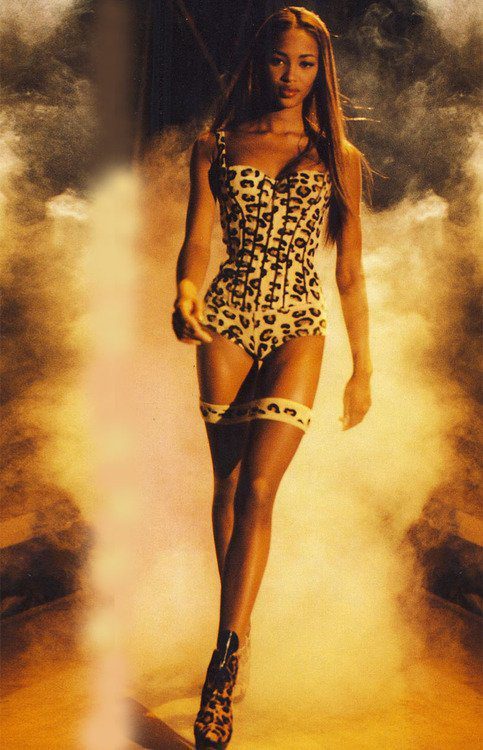

Naomi Campbell wears a leopard-print corset, pants, stockings and heels by Alaïa (AW 1991). Source: Tumblr. A video of her modelling this outfit on the runway is available on Instagram via @unforgettable_runway.

Campbell is an essential part of the Alaïa legacy: taken into his home after her wallet got stolen on her first ever visit to Paris aged sixteen, she became his honorary daughter and always referred to him as “Papa”. Long before Gianni Versace made Campbell the centrepiece of his extravagant shows and campaigns, Alaïa had her strut down his own runway in preppy tops and pleated white skirts. She once even did a little tap dance at the end.

The glamazon par excellence, Campbell was the perfect fit for Alaïa’s designs: statuesque, exotic, and incredibly sexy. Before the bodycon dresses of Hervé Léger, Alaïa was designing pieces that, quite literally, celebrated the female form. The fashion press in the 1980s dubbed him the ‘King of Cling’; and Alice Black, former co-director at the Design Museum in London, which housed an Alaia exhibition in 2017, aptly described his designs as “striking sculpture”.

Alaïa’s designs were so elegant, timeless and unique that he did not need to cultivate much of a personal brand to boost his clothes’ profile. A shy man by nature, he distinguished himself from contemporaries including such bombastic figures as John Galliano and Karl Lagerfeld. He was docile, discreet, and conspicuously gentle, refusing to subscribe to the frenzy of fashion and preferring to take the time to do things well. Indeed, he often presented his collections months after the fashion season had already ended. For lack of a loud personality, he remains relatively unknown outside the fashion coterie – though a name check in cult comedy Clueless (1995) did much to boost his household name status at the time.

In many ways, Alaïa’s accolades outclass his fame. In 1985, he was awarded two fashion Oscars for the ‘Special Jury Prize’ and ‘Creator of the Year’; and after his death in 2017, the British Fashion Awards hosted a special tribute in his honour. Today, his old atelier on the Rue de la Verrerie in Paris has been turned into a house museum, hosting design exhibitions. The most recent one centred on his fruitful and longstanding creative partnership with German fashion photographer, Peter Lindbergh.

Azzedine Alaïa and Linda Spierings shot by Peter Lindbergh. Source: Fondation Azzedine Alaïa.

A postmodern approach

For most designers, stepping into the shoes of the last, great couturier must seem like an insurmountable task. And it felt so for Mulier too, he has confessed – that is, until he earned his stripes. The resounding roar of approval that reverberated around Paris after his debut was indisputable. His approach so far has been to imitate without overthinking. His collections bubble with references to Alaïa’s greatest hits, but they don’t appear constrained or diminished by the ghost of Papa. Discussing his creative process with Another Magazine, Mulier said that he “played around with what [he] thought was Alaïa.” For him, it isn’t not so much an exercise in interpretation as one in favouritism. Some allusions – tight knits and leopard prints – are more obvious than others – the meandering fagoted seams accentuating busts and waists on brief dresses and bodysuits. But it’s precisely this gut-led, instinctive, and postmodern curation of hallmarks – omnipresent but selective – that makes Mulier such a good fit. Indeed, Alaïa’s own approach was much the same.

With the advent of a hotly anticipated swimwear line, Mulier taps into Papa’s backstory by renewing ties with the founder’s Mediterranean roots. But he also explores new avenues for the brand. It’s a commercially savvy and artistically sensitive move, consecrating Mulier’s status as one of the most exciting designers around. Case in point: the lead editorial for the May issue of American Vogue, starring Rihanna and shot by Annie Leibovitz, includes a plethora of recent Alaïa pieces. The cover features the Barbadian superstar in a red lace bodycon suit designed by Mulier, complete with gloves and stilettos in the same palette. She looks positively regal as she arches her baby bump forward. It’s a showstopping image for a woman whose bold sartorial choices have completely reinvented pregnancy-wear. But it’s also the perfect picture of a brand that has forged its legacy in the beautification of women, regardless of age, size, or colour. As Naomi Campbell herself once said: “All women should get to wear Alaïa.”

Read More:

Peyman Khosravani is a global blockchain and digital transformation expert with a passion for marketing, futuristic ideas, analytics insights, startup businesses, and effective communications. He has extensive experience in blockchain and DeFi projects and is committed to using technology to bring justice and fairness to society and promote freedom. Peyman has worked with international organizations to improve digital transformation strategies and data-gathering strategies that help identify customer touchpoints and sources of data that tell the story of what is happening. With his expertise in blockchain, digital transformation, marketing, analytics insights, startup businesses, and effective communications, Peyman is dedicated to helping businesses succeed in the digital age. He believes that technology can be used as a tool for positive change in the world.