Let’s look back on the fabulous history of cross dressing, and its wider implications in contemporary fashion where gender-bending has become mainstream.

Harris Reed, Feb ’22, ’60 Years A Queen’. Photography by Marc Hibbert. Source: Fashion United.

Drag In The Playhouse

The first record of drag’s gender-bending connotation was in 1870, when the Reynolds Newspaper printed the word with reference to a party invitation. “We shall come in drag,’ which means men wearing women’s costumes,” it read. Indeed, drag has always been inextricably linked to costume and performance. The term is believed to have originated in British playhouses back when acting troupes were all male, and those cast in female roles wore petticoats and frocks that would drag across the floor. It may therefore have been in use long before 1870, possibly as early as Shakespeare.

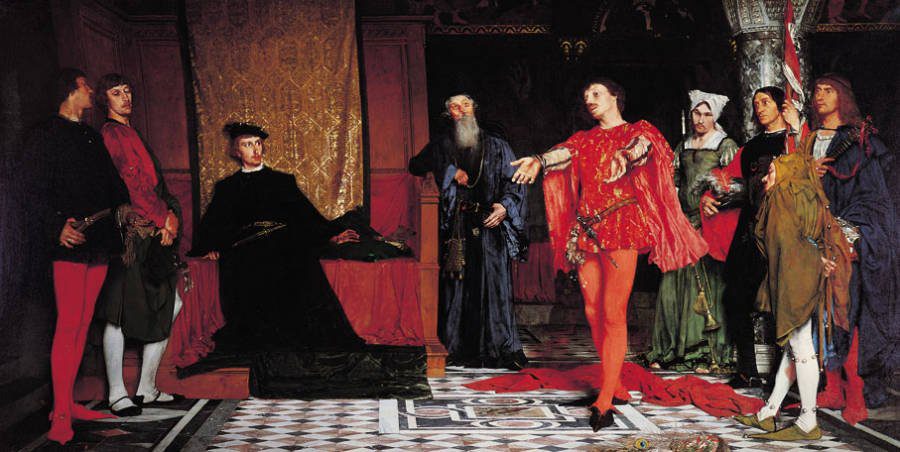

An acting troupe from the Elizabethan era. The third man from the right dresses for his female part. Source: allthatsinteresting

The Politics Of Performance

During the fin de siècle, the term gained wider currency when male performers described the act of dressing up as a female character as “putting on their drags”. Around the same time, more and more women began to perform as male impersonators, with the American vaudeville circuit providing the perfect platform for their self-expression. It was through vaudeville, too, that the first world-famous drag queen, Julian Eltinge, came to be. His popularity extended beyond vaudeville, reaching Hollywood heights. He became the highest paid actor in the world; by the 1920s, his renown was on par with Charlie Chaplain’s. This confirmed drag as a valid (and financially lucrative) art form. As the art of gender impersonation gained acceptance, the term ‘drag’ began to be applied more widely. The coinage of male impersonators as ‘drag kings’ is believed to have emerged around then, with the Harlem Renaissance playing host to celebrated female cross-dressers like Gladys Bentley, who carried herself around in a top hat and tailcoat.

Gladys Bentley circa 1930. Source: Wikipedia.

By the same time, ‘drag’ had also morphed into a term of homosexual identity by becoming part of gay vernacular, possibly via Polari, which drew heavily on theatrical terms. Prohibition cemented the proximity between drag and queer culture when performance was pushed underground into speakeasies, gaining a more transgressive credibility.

From 1930 to 1933, the drag queen phenomenon became known as the ‘Pansy Craze’, with acid-tongued performers like Gene Malin bringing new levels of eccentricity to their performances. Malin bridged the gap between drag and gay culture when he reinvented himself as the tuxedoed MC of Manhattan’s Club Alley, effectively discarding his drag queen persona of Imogene Wilson. His new character was a high-camp, waspish, obviously gay man. “For possibly the first time ever, an entertainer’s entire act revolved around an explicit queerness,” writes Darryl W. Bullock in The Guardian.

The continued criminalisation of homosexuality by the broader culture pushed drag further underground. It wasn’t until the Genovese family of the New York mafia purchased the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village that an outlet appeared for more public displays of queerness, which would eventually snowball into activism and the famous Stonewall riots of 1969. At the forefront of this galvanising movement, drag queen Flawless Sabrina organised multiple pageants across the United States for her community. The seeds that would lead to RuPaul’s Drag Race were sown there and then.

Drag Meets High Fashion

Drag was somewhat sidelined from gay mainstays in the 1970s, no doubt because it went against the newly minted homosexual ideal of virile, masculine beauty (the homoerotic sketches of Tom of Finland come to mind). Yet, somewhat ironically, 70s fashion exploded with gender-bending takes on form and style. With the female smoking suit, Yves Saint Laurent reinvented the uniform of the modern woman, while the provocative editorials of Helmut Newton, fashion photography’s king of kink, endowed these revolutionary designs with potent sexual undertones. Renowned pop stars and musicians pushed the gender-bending agenda further still through the emerging art form of the music video and the advent of glam rock, best epitomised by David Bowie’s sexually liberated, androgynous alterego, Ziggy Stardust. Drag became a cultural commodity rather than a secret subculture – an artistic statement providing societal commentary and reflecting changing attitudes towards gender and performance.

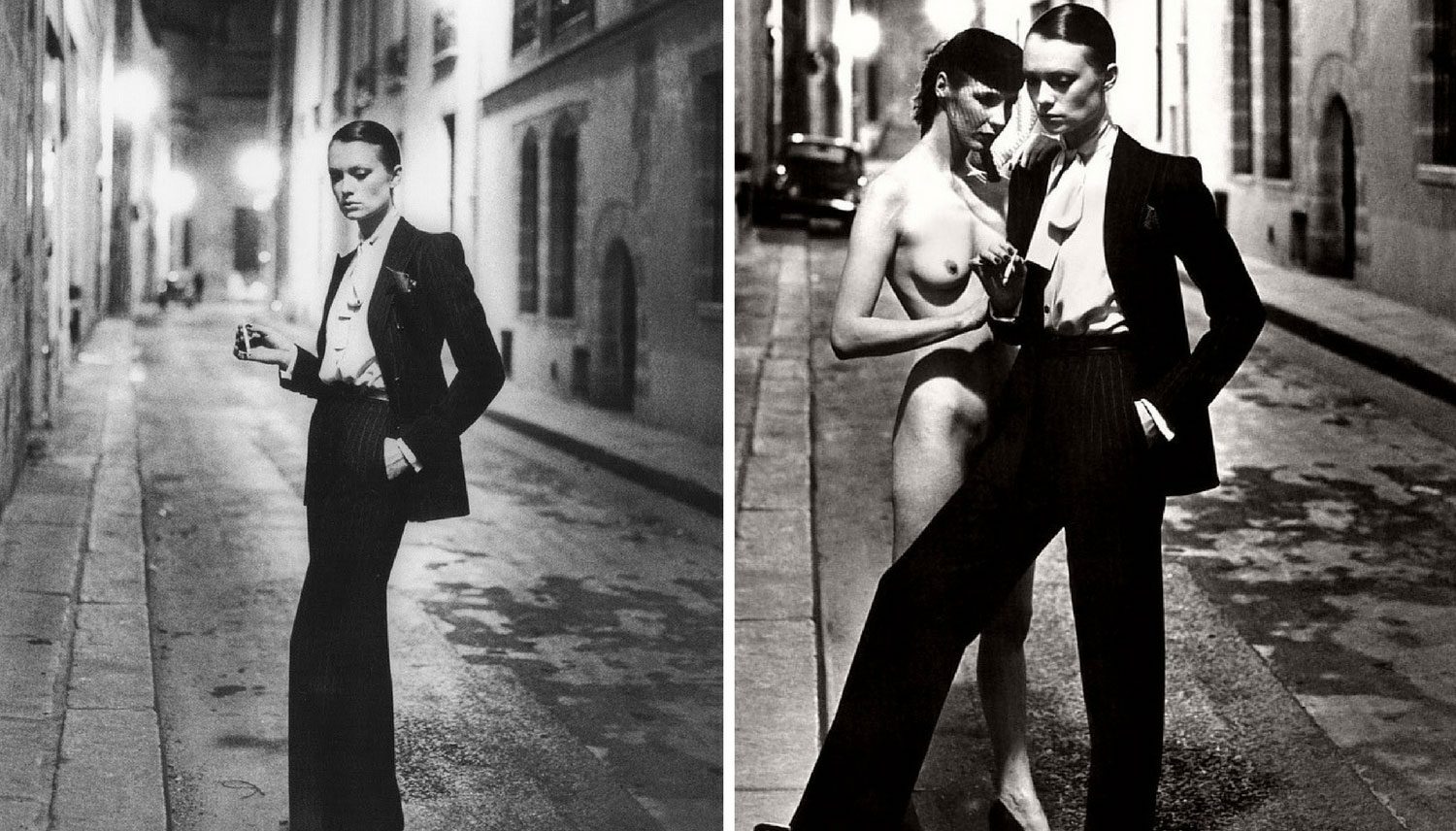

Helmut Newton photographs Saint Laurent’s smoking jacket on an androgynously styled female model, 1975. The addition of a naked woman in the second frame accentuates the gender bending and sexually liberated connotations of this new way of dressing. Source: Code Mag.

The 1980s consolidated the relationship between drag and trendy celebs. The convergence of post-punk and new wave movements in both fashion and music made for a melting pot of flamboyant (and often openly gay) artists. From 70s powerhouses like Elton John and Freddie Mercury to newcomers like Boy George, pop culture flirted with drag more than it ever had before. The cross-dressing influence of the New Romantics, of which Spandau Ballet and Culture Club were the pioneers, persists to this day in the gender-bending designs of creators like Alessandro Michele, who sent Harry Styles to the 2020 Met Gala in a Gucci jumpsuit befitting of the year’s theme: ‘Camp: Notes on Fashion’.

New Romantic band Spandau Ballet. Source: IMDB.

Harry Styles at The Met Gala (2020). Source: WSJ.

Paris Is Burning

While the 1980s championed queer flamboyance on stage, it also penalised homosexuality far worse than previous decades did. As the gay community was ravaged by the AIDS epidemic, conservative politicians parroted a rhetoric of fear, blame and shame, putting stock into homophobic acts, discourse and sentiment. Queer culture was, once more, marginalised and forced underground.

Alliances formed between various oppressed groups, notably among queer black and latino men who created ‘houses’ to take in others yearning for a sense of safety and community. They then adopted the century-old practice of cross-dressing masquerade balls and put a competitive spin on them. Thus, the modern drag show was born.

These shows gained popularity as HIV-awareness and anti-homophobic advocacy grew in tandem. Malcolm McLaren’s 1989 album ‘Waltz Darling’ immersed listeners into the ballroom scene with tracks like ‘Deep in Vogue’, while Madonna’s ‘Vogue’ – the world’s best-selling single of 1990 – brought drag subculture back into the mainstream through a popular dance that recalled the modelling poses featured in the magazine from which it took its name. Later that year, the seminal documentary ‘Paris is Burning’ was released to rave reviews, introducing a wider audience to the ballroom culture of the late 80s, and the gay, trans, African-American and Latino communities that made it shine so brightly.

Still from ‘Paris is Burning’, showing drag queens voguing. Source: The Guardian.

You Better Work

With drag firmly part of the public consciousness, it was only a matter of time before a celebrity drag queen emerged. That title would be claimed by RuPaul Charles, who released his semi-satirical single ‘Supermodel (You Better Work)’ to mainstream success in 1993. The song reached number 2 on the U.S. dance chart and became an instant gay anthem.

François Nars, Verushka, RuPaul, Steven Meisel and Linda Evangelista at an Allure Magazine Party circa 1994. Source: Reddit.

RuPaul has come a long way since name-checking the Holy Trinity of modelling in his disco-inspired house music, but it would be wrong to ignore that the roots of his success lie in fashion commentary and mime. Drag, at its core, is about dressing up, putting on a show, and playing a character. And what is a model if not a freeze-frame actress?

The drag-modelling affinity is something of a dialectic: as time went by, drag queens evolved their style and attitude to match that of the modern woman. The discrete witticisms of Imogene Wilson have given way to more high-octane bravado. Indeed, contemporary drag queen repartee is characterised by excess, speed, volume, and outspokenness. Like other irreverent art forms, drag teases through exaggeration and flirts with self-parody.

These qualities may have their roots in camp, but they are also informed by the era of fashion that made RuPaul into a household name. From Gianni Versace’s pared-back maximalism to François Nars shaving Kristen McMenamy’s eyebrows for an Anna Sui show, the early 90s were all about turning expectations on their heads and knowing it. Claude Montana pursued ever greater experiments with shape for Lanvin; Karl Lagerfeld sent Helena Christensen down the Chanel runway in a mesh top bearing all; and Linda Evangelista’s droll comments issued cultural salvo along with each new haircut, as she flexed her chameleonic physique to elevate modelling into its own art form.

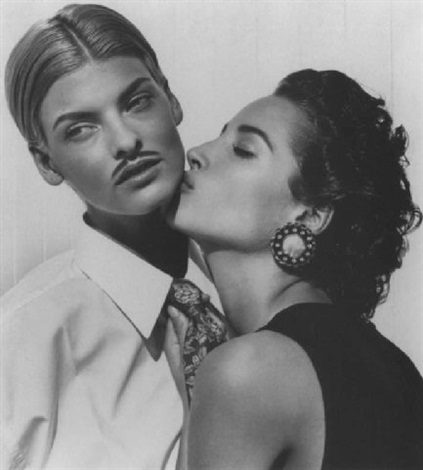

Linda Evangelista poses as a drag king with Christy Turlington for Karl Lagerfeld, 1991. Source: artnet.com

90s fashion was about acknowledging cultural monoliths to better subvert them. RuPaul adopted a similar approach when developing and refining his drag persona. She is both in debt to the legacy of her predecessors and a trendsetter in her own right. She is refined, fearless, and intelligent: but most of all, she is unpredictable. Varium et mutabile semper femina. It’s a quality that RuPaul has learned to extend through mentorship. Case in point: the most popular and entertaining drag queens to emerge from his tutelage are those that throw not only the best shade, but the best curveballs.

There again, this comedic fickleness is inextricably linked to fashion – to the ever-changing cycle of production and consumption that culminates in biannual half-hour shows presenting collections which designers have spent half a year working on. RuPaul is the reason many of us think of drag as an irreverent parody of fashion – in his reality TV series, drag queens compete in runway battles that double down as lip-synching extravaganzas. It’s a theatrical spectacle akin to the couture shows of Thierry Mugler, himself heavily influenced by queer cross-dressing. And like the best fashion shows, the best drag performances carry a message beyond the clothes themselves. Drag is about stories and ideas, which clothes, paired with attitudes, have the power to tell.

RuPaul stalks his own runway, flanked by fellow drag queens. Source: i-D.

Nadja Auermann and Jerry Hall sashay in Haute Couture by Thierry Mugler, 1995. Source: The New York Times.

Border Crossings

Besides Ru-patented pageantry, drag in the present day has edged beyond queer performance. It is, in fact, deftly woven into the cultural fabric, from debates around gender fluidity to the advent of androgynous fashion as championed by cutting-edge designers like Harris Reed and Ludovic de Saint Sernin.

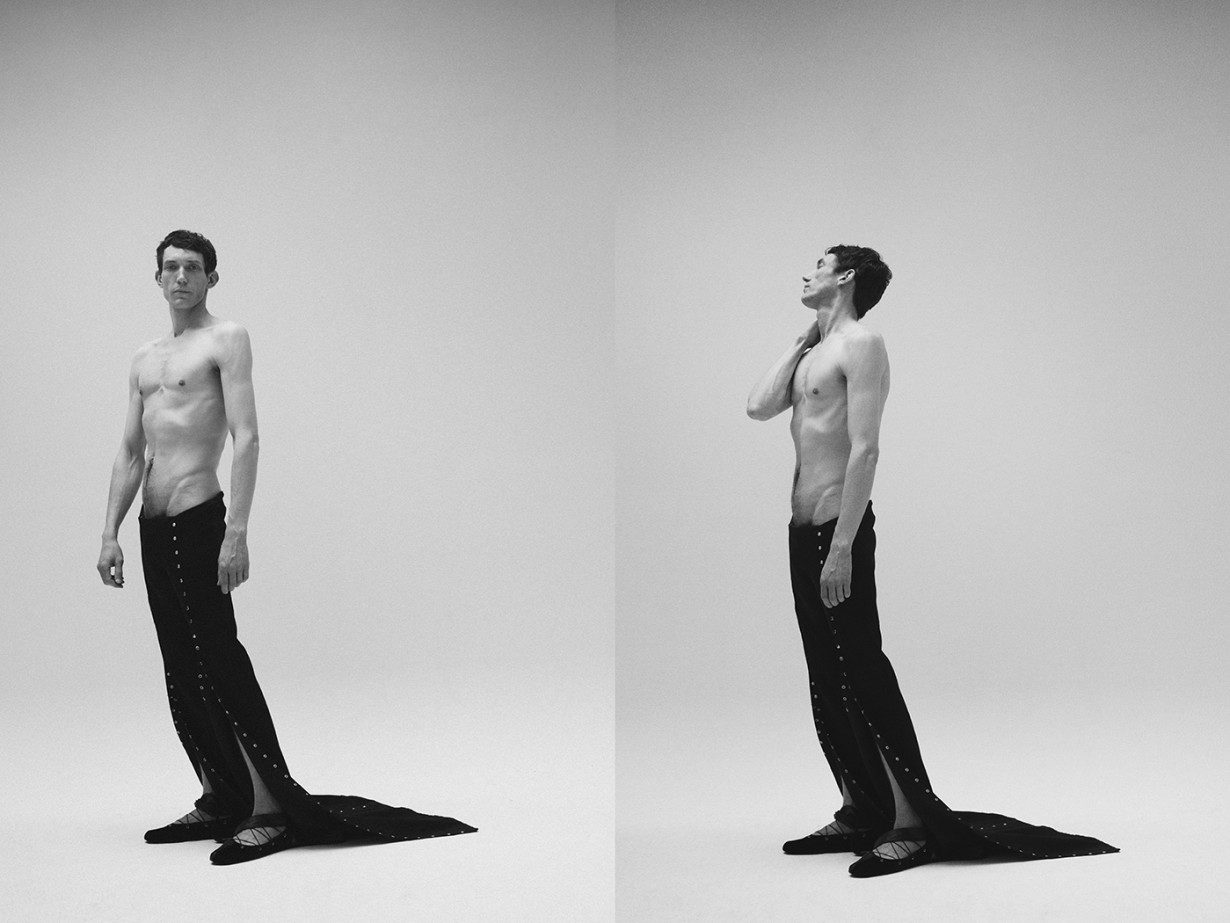

Ludovic de Saint Sernin, winner of the 2018 LVMH prize. Source: The Last Magazine.

As fashion continues to redraw the lines of masculinity and femininity, it returns time and time again to drag for inspiration. To describe the history of drag as sartorial is not to deny its political or cultural potency. Rather, it recognises that clothes have the power to affect societal change, particularly when worn in deliberately performative and transgressive ways.

Read More:

Peyman Khosravani is a global blockchain and digital transformation expert with a passion for marketing, futuristic ideas, analytics insights, startup businesses, and effective communications. He has extensive experience in blockchain and DeFi projects and is committed to using technology to bring justice and fairness to society and promote freedom. Peyman has worked with international organizations to improve digital transformation strategies and data-gathering strategies that help identify customer touchpoints and sources of data that tell the story of what is happening. With his expertise in blockchain, digital transformation, marketing, analytics insights, startup businesses, and effective communications, Peyman is dedicated to helping businesses succeed in the digital age. He believes that technology can be used as a tool for positive change in the world.