The history of Western fashion has been continuously shaped and informed by the Catholic Imagination; by the parables and scriptures of the Old and New Testaments that underpin our social fabric and civil codes. Whether fashion designers seek to capture the zeitgeist or escape it, their debt to the context and the climate that inspire their craft is equal. Garments hold a mirror up to culture, and few cultural influences have been more potent and pervasive than Christianity. And though religion’s more aggressive orthodoxies have dwindled amongst liberal communities in the past fifty years, the ubiquity of the Catholic imagination in clothing continues to shine. Even today, modern interpretations of religious attire — such as elegantly designed church dresses— serve as a testament to the lasting influence of faith on fashion.

Rihanna reigns in a Pope-inspired dress at the 2018 Met Gala. Source: Twitter (@RihannaDaily)

The past two decades have seen traditional Christian symbolism reclaimed by alternative subcultures. As the conversation around cultural appropriation became more widespread in the early 2010s, white middle-class hipsters swapped dreadlocks and indiginous-print trousers for less offensive crucifix necklaces. The dialogue between Christianity and high fashion is more active and elaborate still. Vetted by the Vatican, “Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” was the theme of the 2018 Met Gala. The party saw Rihanna don a papal outfit complete with a mitre, Ariana Grande enveloped in a gown printed with the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and Zendaya emblazoned in mock-mediaeval armour à la Joan of Arc. The costumes were fabulous, excessive, caricatural, and tapped into a sartorial heritage dating back to the Crucifixion.

For over two millennia, Christianity has dictated what’s hot in the wardrobe department. Before couturiers became our style pundits, priests and pontiffs played a vital role. It wasn’t quite as direct as it might have been in the twentieth century couture salon; but by entertaining close rapports with European heads of state, Pope after Pope allowed the lavish costumes in which the Royal families posed for portraits to serve as symbols not only of a nation, but of the Church too. This created an indelible bond between religion, fashion, and elitism: one that has been upheld by Catholicism in particular. Ahead of the 2018 Met Gala, Andrew Bolton, Wendy Yu Curator in Charge at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, explained that:

Throughout the history of the Catholic Church, dress has affirmed religious allegiances, asserted religious differences, and functioned to distinguish hierarchies as well as gender.

When the wars of religion broke out in the sixteenth century, one of Protestantism’s harshest critiques of the Roman Catholic Church was of the hypocrisy inherent in its adoration of expensive ornaments intended to represent Christ. This ran counter to two Biblical prescriptions: a life of humility and an avoidance of idolatry. Centuries on, the Catholic clergy was still a wealthy set preaching in highly stylised churches, second only to the nobility in social ranking in a pre-industrial Europe. Fast forward to the twenty-first century, and the upper echelons of the Holy See remain immaculately dressed in expensive garb, with Pope Benedict XVI reportedly having a penchant for Prada slippers.

The relationship between fashion and Catholicism goes both ways; and while some designers are only passively influenced by religion, many actively acknowledge its inspirational qualities. Luminaries from Jean Paul Gaultier to Domenico Dolce and Steffano Gabbana have drawn on the pictorial splendour of Catholic iconography, while irreverent postmodernists like Rick Owens have staged entire runway shows around a single biblical allusion. His Autumn-Winter 2021 show was named after Gethsemane – the garden where Jesus prayed the night before his death. Expanding on his title choice, Owens described the biblical grove as “a place of uneasy repose and disquiet before final reckoning” (i-D). At a time in history marked by high geopolitical tension and a fragile world economy, Owens drew on a Christian story of betrayal, forgiveness and rebirth to present a collection marked by dark, morose tones and pre-apocalyptic equipment. His shearling jackets extended upwards into balaclavas while sleeves stretched down into leathery gloves.

Backstage at Dolce & Gabbana Autumn-Winter 2013. Source: behindthescenesmakeup.com

Jean Paul Gaultier Spring-Summer 2007, Haute Couture. Source: Instagram (@banannasui)

Rick Owens Autumn-Winter 2021. Source: designscene.net (©RICK OWENS)

Religion, as Owens suggests, has always been a refuge: a narrative that offers meaning when science and rationality cannot. Fashion is much the same. It offers an escape route: a means of disappearing into the imagination of a designer who believes in the healing power of beauty. As the late Thierry Mugler famously quipped: “Beauty can save the world.”

Fashion and religion go hand in hand in more ways than one, and it’s not atypical for reputable fashion personalities to be deified. In the past six months alone, the deaths of Virgil Abloh, Thierry Mugler, André Leon Talley and Patrick Demarchelier all elicited grief-stricken online tributes from former collaborators, many of whom played up the mythology of their departed colleagues. Beyond the aesthetic influence of the Catholic faith, fashion is also marked by a similarly zealous performativity.

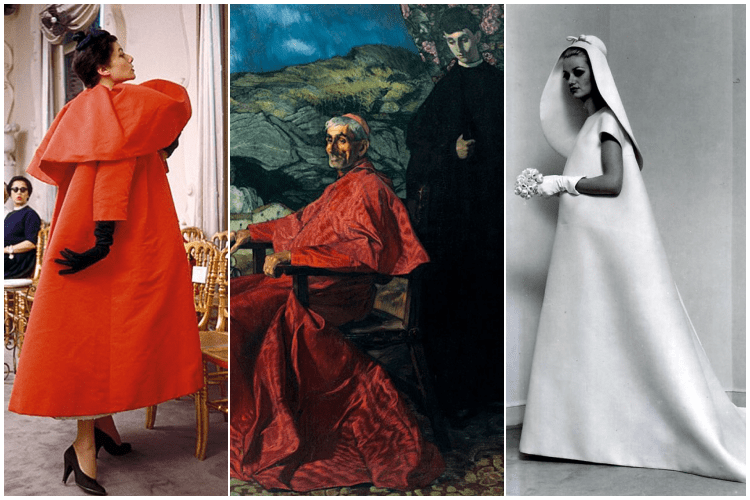

It’s this dual mirroring of style and behaviour that has kept the rapport between Catholicism and Couture so current and symbiotic to this very day. But beyond the anthropological explanation, there’s also a sociological one. Historically, high fashion has been the privy of French and Italian maisons like Dior, Balmain, Schiaparelli, and Valentino. And because these are predominantly Catholic countries, it makes sense that such a cultural influence should play out not only in their collections, but also in those of other designers whom they inspire. The number of trailblazing fashion legends brought up in the Catholic tradition cannot be understated, including such storied names as Yves Saint Laurent, Miuccia Prada, Christian Lacroix, and Gianni and Donatella Versace. The most poignant example of Catholic imagination, however, is found neither in a Frenchman nor an Italian, but in a Spaniard: Cristóbal Balenciaga was renowned for his austere dresses, borrowing their form heavily from parish priests, friars and nuns.

Left and Right: Designs of monastic inspiration by Cristóbal Balenciaga. Centre: ‘El Cardenal’, by Ignacio Zuloaga. Source: magazinehorse.com

But perhaps the most compelling argument for the symbiosis between fashion and the Catholic imagination is their mutual propensity for storytelling. Both offer substance through style and meaning through the promise of beatitude. Fashion, like Christianity, is anchored in the theme of rebirth, and invites its disciples on a journey of self-discovery through reinvention.

William Hosie is a writer and editor with a keen interest in fashion, design and art, earning a Double First from Magdalen College, Oxford in 2020.