British designer Mary Quant, who harnessed youth culture and revolutionised Sixties’ fashion with playful, liberating looks like minis, tights, hot pants, dress-and-knickers and a cosmetic line that complemented the racy styles, died aged 93 at her home in Surrey, in southern England. Her visionary aesthetic, and consequent runaway success of her hip boutique, transformed it into an empire.

Mary Quant studied illustration at Goldsmiths and graduated in 1953 with a diploma in art education, following which she interned with milliner Erik. In 1955, her late husband Alexander Plunket Greene purchased Markham House on King’s Road in Chelsea, London, a neighbourhood frequented by the “Chelsea Set”. Here Quant, Plunket Greene and a friend, lawyer-turned-photographer Archie McNair, opened a restaurant and a boutique. Subsequently, loud music, free cocktails, creative window displays and extended opening hours created a ‘scene’ that often winded up at midnight. It was the place to shop and hang out in London. By the early Sixties, the collections were a rage with the celebrity set and were featured in Harper’s Bazaar.

She lived a full life. Per The Guardian, “By the late 50s Quant had synthesised her Chelsea girl look from elements of left bank kooky beatnik and practical details of American sportswear, plus her preference for vulgarity over good taste. Then she began supplementing it with memories of her ideal – a girl of about eight glimpsed during a childhood dancing class, who had a Dutch doll haircut and wore a dark skinny knit, very short pleated skirt, white socks and black patent shoes that focused on the boot button of their ankle strap. Quant made similar clothes the basis of the dolly-bird look of the 60s.”

She worked hard for the money. Quant was a self-taught designer, who attended evening classes on cutting and used printed patterns to achieve the looks she envisioned. She also initiated a unique production cycle wherein the day’s sales at her boutique paid for the fabrics that she transformed overnight into new apparel for the following day. This retail strategy ensured that her fashion brand always had fresh, unique looks. Mary Quant’s design was free from the constraints of old rules. Her mini and other irreverent looks were critical to the development of the ‘Swinging Sixties’. Most importantly, they were affordable, democratising fashion for a generation itching to escape the confines of their mother’s conservative wardrobes.

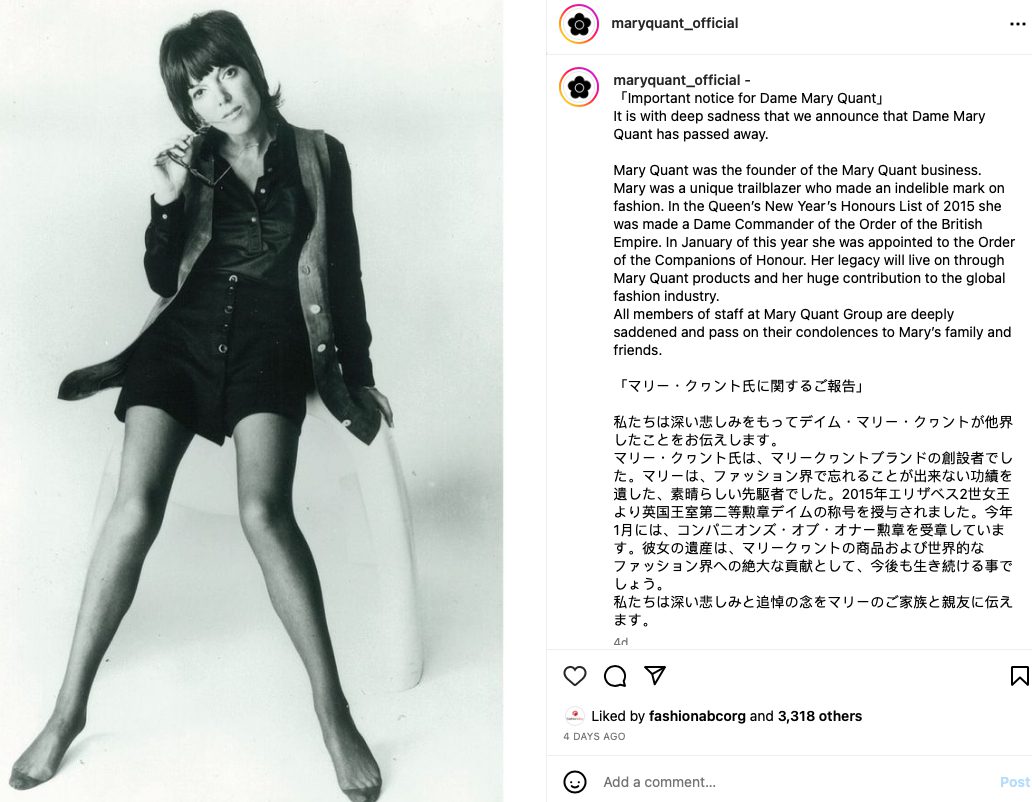

Image Source: Instagram account of Mary Quant

Mary Quant cosmetics were lunched in 1966 and were more unique and flamboyant than her fashion brand. In fact, she designed the cosmetic containers as ornaments for dressing tables, with lipsticks and compacts modelled on eighteenth-century boudoir trinkets! Other examples of Quant’s irreverent designs are her line of men’s cardigans long enough to wear as dresses and white plastic collars used to brighten up sweaters and dresses. By 1957, demand for Quant’s collections led to the opening of a second store on King’s Road. In the late Sixties, Quant designed the ‘skinny rib’ sweater and short shorts that were the forerunner of hot-pants! She was the first designer to use PVC, creating ‘wet look’ styles and weatherproof boots. Her relaxed practical everyday wear too became a rage as she paired short tunic dresses with bright coloured tights. In the late Sixties, Quant designed short shorts that were the forerunner of hot pants.

Image Source: instagram account of Mary Quant

In 1962, she signed a deal with American department-store chain JC Penney. The following year, Mary Quant Limited expanded into the UK mass market with a new, affordable diffusion line, Ginger Group. The following year, she opened her third shop in London’s New Bond Street. In 1966, Mary recognised the need gap for a new style of makeup to go with the new bolder fashion. This development made waves throughout the world, particularly in Japan. Mary made the first of many visits to Japan in 1972, which lead to Japanese influences appearing in her designs. In 1988, she designed the interiors of the Mini. The seats were designed with black and white stripes offset with red trimming and seat-belts; the steering-wheel had the designers’ signature daisy and the bonnet badge had “Mary Quant” written on it.

“Over and again I was told I was responsible for the offbeat clothes that became known as the Chelsea Look . . . people either loved them or hated them. But, in fact, no one designer is ever responsible for such a revolution. All a designer can do is to anticipate a mood before people realize they’re bored with what they’ve already got.” An excerpt from her book.

Through the Seventies and Eighties she concentrated on household goods and make-up rather than just her clothing lines. In 2000, she resigned as director of Mary Quant Ltd after a buy-out by her Japanese licensees but has gone down in history as the pioneer of a rebellious fashion movement. So it’s no wonder she was honoured with prolific awards throughout her illustrious career. In 1966, Mary Quant was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire for her outstanding contribution to the fashion industry. In 1990, she won Hall of Fame Award of the British Fashion Council and was appointed Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 2015 New Year Honours for services to British fashion. Quant is also a Fellow of the Chartered Society of Designers and winner of their Minerva Medal.

“The celebrity designer is an accepted part of the modern fashion system today, but Mary was rare in the ’60s as a brand ambassador for her own clothes and brand,” Jenny Lister, a co-curator of a 2019 retrospective of Ms. Quant’s work at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, told The New York Times. “She didn’t just sell quirky British cool, she actually was quirky British cool, and the ultimate Chelsea girl.”

Sadly, Mary Quant eventually resigned as director of the company and lost control in 2000 of her name and her daisy logo, but stayed as consultant. We may not be donning PVC shifts and go-go boots much anymore, but the free-spirited fashion and beauty trend continues to dominate the runways. Late fashion legend Mary Quant’s influence lives on and feels as fresh as it did in 1955.

Jasmeen Dugal is Associate Editor at FashionABC, contributing her insights on fashion, technology, and sustainability. She brings with herself more than two decades of editorial experience, working for national newspapers and luxury magazines in India.

Jasmeen Dugal has worked with exchange4media as a senior writer contributing articles on the country’s advertising and marketing movements, and then with Condenast India as Net Editor where she helmed Vogue India’s official website in terms of design, layout and daily content. Besides this, she is also an entrepreneur running her own luxury portal, Explosivefashion, which highlights the latest in luxury fashion and hospitality.