Summary

Ann Cole Lowe was the first African American to become a noted fashion designer. Lowe’s one-of-a-kind designs were a favorite among high society matrons from the 1920s to the 1960s. She was best known for designing the ivory silk taffeta wedding dress worn by Jacqueline Bouvier when she married John F. Kennedy in 1953.

Biography

Early Years

Lowe was born in rural Clayton, Alabama, under the oppressive thumb of Jim Crow laws in 1898.She was the great granddaughter of a slave woman and an Alabama plantation owner.She had an older sister, Sallie.Her grandmother Georgia’s dexterity for sewing was learned on Tompkins Plantation where she was born into slavery.

Her mother Ann and grandmother Georgia, both of whom worked as seamstresses for the first families of Montgomery and other members of high society. Lowe’s mother died when Lowe was 16 years old. At the time of her death, Lowe’s mother had been working on four ball gowns for the First Lady of Alabama, Elizabeth Kirkman O’Neal. Using the skills she learned from her mother and grandmother, Lowe finished the dresses.

Personal Life

In 1912, she married Lee Cohen, with whom she had a son, Arthur Lee who later worked as Lowe’s business partner until his death from a car accident in 1958.After her marriage, Lowe’s husband wanted her to give up working as a seamstress. She complied for a time but left him after she was hired to design a wedding dress for a woman in Florida.

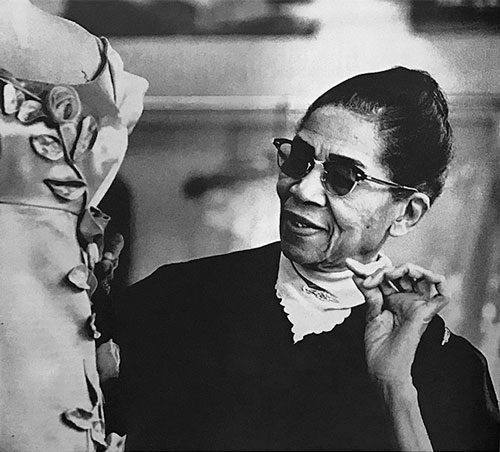

Image source: gal-dem.com

She married for a second time but that marriage also ended. Lowe later adopted a daughter, Ruth Alexander.

Since the 1930s, Lowe lived in an apartment on Manhattan Avenue in Harlem. Her older sister Sallie later lived with her. Both were members of St. Marks United Methodist Church.

Death

Lowe died at her daughter’s home in Queens on February 25, 1981, after an extended illness. Her funeral was held at St. Marks United Methodist Church on March 3.

Fashion Career

In 1917, Lowe and her son moved to New York City, where she enrolled at S.T. Taylor Design School. As the school was segregated, Lowe was required to attend classes in a room alone. She returned to Tampa in 1919 and saw an opportunity to capitalize on the city’s yearly, celebration known as the Gasparilla Ball, where a court and queen is crowned and week long festivities. The following year, she opened her first dress salon, “Annie Cohen”. The salon catered to members of high society and quickly became a success.

By 1928, Ann was eager to fulfill her dream as a fashion designer in New York City. As the dressmaking darling of Tampa’s social-register, she managed to save $20,000.

In order to make ends meet, she had to put her independent design career on hold and take jobs by designing anonymously for other labels and department stores such as Henri Bendel, Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue and Chez Sonia. In 1946, she designed the dress that Olivia de Havilland wore to accept the Academy Award for Best Actress for To Each His Own, although the name on the dress was Sonia Rosenberg.

By 1950, the stepping stones in Lowe’s career began to align and she finally launched her own label,Ann Lowe’s Gowns, with a small storefront on Lexington Avenue in New York City. Her one-of-a-kind designs made from the finest fabrics were an immediate success and attracted many wealthy, high society clients.

One design element she was known for were her fine handwork, signature flowers, and trapunto technique.Throughout her career, Lowe was known for being highly selective in choosing her clientele. Over the course of her career, Lowe created designs for several generations of the Auchinclosses, the Rockefellers, the Lodges, the Du Ponts, the Posts and the Biddles.

In 1953, Lowe received her most important commission to date – she was hired to design Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding gown as well as the dresses for her bridal party. Ann derived inspiration from the gowns she remembered her grandmother made for Montgomery’s Southern belles.

Lowe was chosen by Janet Auchincloss, the mother of Jacqueline Bouvier, who had previously commissioned Lowe to design the wedding dress she wore when she married Hugh D. Auchincloss in 1942. The dress, which cost $500 (approximately $5,000 today), was described in detail in The New York Times’s coverage of the wedding.While the Bouvier-Kennedy wedding was a highly publicized event, Lowe did not receive public credit for her work.

Image source: anthology-magazine.com

Throughout her career, Lowe continued to work for wealthy clientele who often talked her out of charging hundreds of dollars for her designs. After paying her staff, she often failed to make a profit on her designs. Lowe later admitted that at the height of her career, she was virtually broke.In 1961 she received the Couturier of the Year award but in 1962, she lost her salon in New York City after failing to pay taxes.

That same year, Lowe had to undergo surgery to remove her left eye due from complications with glaucoma. When she emerged from the hospital she discovered that her IRS debt had been paid in full by an anonymous friend. Soon after, she developed cataract in her left eye which was saved after surgery. In 1968, she opened a new store, Ann Lowe Originals, on Madison Avenue. She retired in 1972.

Renewed interest by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture as well as New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art has finally given her the place in history she deserved. A collection of five of Ann Lowe’s designs are held at the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Three are on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC. Several others were included in an exhibition on black fashion at the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology in Manhattan in December 2016.A children’s book, Fancy Party Gowns: The Story of Ann Cole Lowe written by Deborah Blumenthal was published in 2017.